As someone who enjoys doing pushups, I've always wondered what percentage of a person's body weight is being "pushed-up".

As a Physiotherapist, I often use push-ups - and their variations, to build and re-build strong and stable shoulders and surrounding tissue. Conceptually, I understand how to progress and regress a push-up, but I've never known the true numbers.

That is, until, I recently came across this study which looked at quantifying the ground reaction force associated with different push-up positions.

Let's take a quick look.

Study Design

- 23 participants

- 14 men and 9 women

- Each recreationally fit

- Use of force plates to record ground reaction forces (GRF)

Each participant performed six different push-up variations with standardised hand placements and push-up cadence:

- Regular push-up

- Kneeling push-up

- Incline push-up 30cm

- Incline push-up 60cm

- Decline push-up 30cm

- Decline push-up 60cm

How "Heavy" Are Push-Ups?

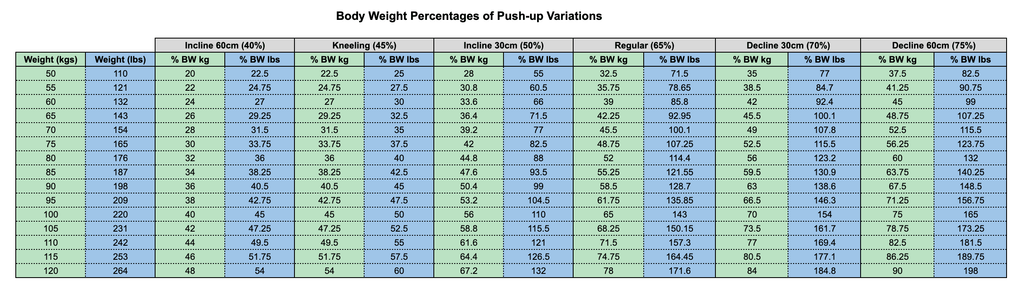

As you can see via the infographic summary above, the numbers follow a very logical progression. The more upright we are, the less percentage of body weight is used. It's worth noting that these results were not affected by gender or height differences.

Incline push-ups at 60cm and 30cm only account for approximately 40% and 55% of a person's body weight respectfully.

Interestingly, a kneeling push-up is similar to pushing 50% of a person's body weight, which is good to know considering this is often the push-up of choice for some women.

For me, I find it interesting that a regular push-up equates to 65% of a person's body weight. As an 80kg (176lb) man, this means I'm "pushing-up" approximately 52kg (114.4lb) with each repetition.

Conversely, the closer we progress to an upside-down position, the closer we get to 100% body weight. Decline push-ups at 30cm and 60cm are similar to 70%a and 75% body weight respectively.

It's probably also worth noting that a complete, free-standing handstand push-up might be the closest thing we can get to 100% body weight (allowing for hand and forearm weight), but the demands here are obviously shifted to different areas than the variations listed above.

Limitations of the Study

As with every piece of research, it's important to consider its limitations before generalising to a wider population. These may compromise our ability to generalize any findings to the wider population.

The following are things to consider:

- A relatively small study of 23 participants

- Participants were recreationally fit meaning it might harder to generalise to 'unfit' or 'highly' fit populations.

More research would be great to see across larger population numbers and broader fitness spectrums and genres, but it does present a strong case to consider nonetheless.

Related: Here's why I'm at odds with evidence-based practice.

Conclusion

Push-ups are a great exercise for all fitness levels and capacities. As a Physiotherapist, I also find them to be a highly valuable and scalable rehabilitation tool for my patients.

Quantifying body weight percentages of each push-variation can help us better tailor and progress our programs to more efficiently reach our fitness and rehab goals.

- Grant

Article Link:

Ebben, W. P., Wurm, B., VanderZanden, T. L., Spadavecchia, M. L., Durocher, J. J., Bickham, C. T., & Petushek, E. J. (2011). Kinetic Analysis of Several Variations of Push-Ups. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 25(10), 2891–2894. https://doi.org/10.1519/jsc.0b013e31820c8587

If you'd like help trying to uncover the underlying cause of your pain or dysfunction, consider booking in an online Telehealth consultation with Grant here!