The hamstring injury is far too common. Despite the time and effort, we devote to its prevention and treatment it's still so frequent.

In the Australian Football League (AFL) alone, new hamstring injury rates have barely shifted for the best part of six years.

This lack of progress speaks to a significant gap in our thinking. Perhaps an angle we aren't considering or respecting enough. We must be missing something.

As a Physiotherapist, you have the opportunity to refine your pattern recognition skills. The more dysfunction you see the easier it is to link things together. Things relatively obscure and harmless in isolation, but form the foundation of injury when the necessary perspective is applied.

Clinically, it seems we are yet to solve the hamstring injury puzzle because we too often neglect the lower back.

In this article, I hope to use the hamstring struggles of former AFL player, Cyril Rioli in a positive way to highlight what I’m finding. I'm certainly not the first to explore the impact of low back dysfunction on a hamstring injury. But I don't think we understand it's impact enough.

So whether you're as injury-prone as the freakishly talented Cyril Rioli or just looking to stay fit and healthy, let's explore why the low back is so important with a hamstring injury.

Cyril Rioli's Hamstring Injury History

Cyril Rioli was an absolute joy to watch play football.

Whether you understand the sport of AFL or not, just take a look at what this man could do on the football field.

He was insanely quick, agile and immensely gifted. In terms of injury, Cyril's athletic gifts were hampered by consistent hamstring injuries.

Over a six-year stretch, he succumbed to seven hamstring tears before getting on top of them.

After playing every game in a brilliant first year in the AFL (2008) here's a breakdown of what happened next:

Interestingly, the Hawthorn medical team tried three specific approaches in the hope of curing his issues.

They were:

- Altering his running technique (here)

- Changing his role in the side to one less physically demanding (here)

- More targeted strength work through his trunk, hips and legs (here)

It was not until the medical team doubled down on lower body strength-work that Cyril seemingly conquered his hamstring injuries. He was hamstring injury-free until he retired in 2018.

This is an important point to consider. More strength seemed to do the trick. But herein lies the problem. From what I see clinically, strength may just create a bigger buffer against any underlying dysfunction. It may not offer a solution.

And I'll explain why in a minute.

The Hamstrings

To get a little technical, the hamstrings are the three main muscles at the back of your thigh. They originate from the sit bone at the bottom of your pelvis and insert below the knee at the back. There is one major hamstring muscle on the outer side (Biceps Femoris) and two on the inner side (Semimembranosus, Semitendinosus).

Hamstring Function

Functionally, hamstrings bend the knee and extend the hip. They also help lower a straight back when leaning or bending over.

They also seem to get injured a lot!

So much so that most athletes would have suffered a hamstring injury at some point - whether it be a tight hamstring, hamstring tear, hamstring tendonitis or a rupture. It's a prolific beast.

Hamstring Injury in the AFL

In the AFL, the length of time out injured and the rate of re-occurrence has been similar for seven to eight seasons now. Things are certainly better than a decade ago, but the point remains the same. We aren't solving the issue. This is despite AFL athletes being some of the best conditioned in the world and being conditioned by some the best in the world.

Here's GWS Giants' viral video of Dylan Shiel doing a 'razor curl'.

It's great to watch. Give it a go if you can, it's hard to comprehend how good he is without understanding how bad the rest of us probably are. Interestingly, he has still had hamstring issues of his own - despite how strong he clearly is.

Furthermore, a look at the official AFL injury list on any given week reveals approximately 20-25 players affected by a hamstring injury.

Each week is a revolving door of hamstring dysfunction and rehabilitation.

Hamstring Injury Cause

If you were to poll every Health Professional about the cause of a hamstring injury, I'd imagine there won’t be a consensus. Most likely because I don't think we currently know. I mean if we did, why aren't we seeing fewer hamstring injuries?

We know a hell of a lot about them, but not necessarily the root cause. We can predict what you might be doing when you hurt yourself, but not the fundamentals of why.

The following are common risk factors associated with hamstring injury:

- Activities and sports associated with running and sprinting

- Poor warm-up

- Prior hamstring injury

- Poor hamstring strength

- Poor hamstring flexibility

- Gluteal weakness

- Fatigue

When trying to understand the injury we look for tightness and weakness involving the hamstrings, quadriceps, and gluteals. The term “imbalance” is often associated with these muscles in an attempt to explain why a perfectly good hamstring can injure.

Hamstring Injury Treatment

A typical treatment for a hamstring injury may look like this:

- Reduce pain

- Reduce swelling

- Strengthening of the hamstrings, gluteals and "core"

- Muscle stretches

- Graduated return to your previous sport or activity

With any luck, you'll be back before you know it.

Yet despite everything we currently understand about hamstring injury and rehabilitation we may, in my clinical experience, be missing the bigger picture here.

Sometimes I feel that we don’t take a big enough step back and ask why the hamstring becomes dysfunctional in the first place. What causes its failure?

And this is where I think it gets very interesting.

What I’m Finding Clinically

As mentioned before Physiotherapists have the capacity to recognize and explore patterns. If someone comes in with a hamstring injury I can take that step back, poke around and see what might be wrong with the system as a whole.

More importantly, I can treat what I find and re-assess immediately. I can test and re-test the same idea over and over again with different patients to establish validity. Not necessarily one dictated by years of traditional research, but one hardened by years of clinical exploration and results.

With that in mind, I find one thing intrinsically linked to hamstring injuries.

Low back dysfunction.

The Low Back's Role in Hamstring Injury

The longer I’ve been hunting for solutions to physical problems, the more I keep coming back to the spine.

I've already covered the spine's role in Patella Tendonitis, Tennis Elbow and Osgood Schlatter Disease on the blog, but the list goes on.

A “back-related” hamstring injury will not be news to some, but it will be to others.

Over the last few years, each hamstring injury I've treated also had accompanying low back dysfunction. Interestingly, I'm not talking about pain and overt discomfort, but the dysfunction you have to go looking for.

This clearly doesn't mean everyone with a suspect low back will go on to enjoy a hamstring injury, but once injured hindsight seems to speak for itself.

So, what kind of low back dysfunction are we talking about here?

Joint Stiffness

Anatomically speaking, most joint stiffness seems to be around the L4/5/S1 area.

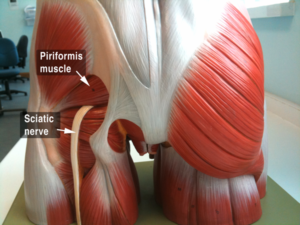

The nerds may also recognize this as the general origin of the Sciatic Nerve. For those unaware, the Sciatic Nerve leaves the spine and travels straight down the back of the leg among the hamstrings.

If the nerve becomes restricted at the spine it may not "floss" as it's supposed to. This may create the potential for mechanical dysfunction along any part of its path down the leg.

This is an important feature because we often mistake Sciatic Nerve tightness for hamstring tightness.

For context, try this:

- Stand up, put your heel onto a bench and lean forward in a typical hamstring stretch position.

- Take note of how it feels and how far you go.

- Lie down and gently press a foam roller/rolled up towel into your lower back.

- Take the time to stop and let the roller press into any stiffness you find. Spend a few minutes on each spot

- Stand up again and re-test the original hamstring stretch

With any luck, it should have immediately improved.

Now, try this:

- Bend over and touch your toes.

- Again take note of how it feels and how far you can go.

- Lie on your back and bend one hip and knee to 90 degrees with your ankle bent back as far as it will go.

- Clasp behind your thigh with both hands and gently straighten your leg from the knee.

- Straighten your leg fully then come down again.

- Repeat this fifteen times (with your foot bent back the whole time).

- Stand up, bend over again and compare.

You should feel immediately better. Pretty cool, right?

Both examples highlight how low back stiffness can compromise "flexibility" via neural tension. The first tries to free the nerve up at its spinal origin and the second via its course down the leg.

The Sciatic Nerve should floss freely at all times. Clinically, any restriction seems to have a negative effect on the function of the back of the leg and our precious hamstrings.

Consider for a moment what effect low back stiffness/neural tension may have on the hamstrings when sprinting at top speed. Now imagine someone like Cyril at top speed…

Poor Spinal Stabilization

When discussing trunk stabilization it's important to distinguish this from “core strength”.

Stabilization refers to how well your trunk musculature activates during movement to reinforce the spine. This is different from how strong it is. It may sound subtle but it's a very important distinction. Being able to hold a plank for two minutes is great, less so if your body can't use it when applicable.

Clinically, it’s this activation or lack thereof that may set your hamstrings up to fail.

It seems that a poorly stabilized spine will recruit other tissue - hello hamstrings, to help out. Essentially, the body will sacrifice peripheral mechanics to prioritize central stability. In other words, the spine is more important than our legs.

For more context, try this:

- Lie down once again with your hip and knee at 90 degrees.

- Keeping your thigh where it is and straighten your knee.

- Use the roof to get a sense of how far go, then come back down again.

- This time, consciously activate your trunk and brace your spine. (Step-by-step guide coming soon)

- Re-straighten your leg again.

As with the other tests, you should see the leg now goes higher the second time.

This is a great example of how a well-braced spine allows the hamstrings to function more normally.

Poor bracing may leave your hamstrings at a constant mechanical disadvantage - regardless of how strong your trunk is.

Now put this into someone like Cyril at top speed...

The Cause Of Low Back Stiffness and Deactivation

To put all this in perspective, let’s take the conversation further.

I'll ask two crucial questions.

- Why does a lower back that's designed to be supple and mobile get stiff?

- Why does a trunk that’s inherently designed to self-stabilize become poor at it?

These questions lead us to one of the most boring and unsexy topics of conversation in the history of the universe (and throughout all time and space).

Posture.

Now, this isn't a new concept to anyone. We've all been pestered about it before.

It's also a hotly debated topic within the medical industry. As it stands there's currently little evidence to suggest poor posture leads to anything concrete in the way of back pain. But it's not hard to connect the dots to poor function. The kind that sets the hamstrings up for injury and dysfunction. In fact, it's blatantly obvious if you're looking for it.

Clinically, sitting postures are the most relevant. If for no other reason than they're such an ingrained part of modern living.

Everyone knows what the couch feels like. We all have to sit in a car or use a computer. Being an elite athlete certainly doesn't give you immunity either. Someone like Cyril Rioli still has to sit in team meetings and fly interstate. He's also still exposed to the same things we are outside of football.

Slouching Is Pure Evil Over Time

Like most activities, it's not what you do that matters, it's how you do it.

And although the sedentary aspect of sitting is bad enough it's the lounging or slouching that takes the biggest toll here. Not an immediate one but more a “death by a thousand cuts”.

Forcing a constant hinge in your back will ask your spine to reinforce against it over time. Hello, stiffness.

Similarly, slouching is not an active position. It's a passive one. So after years of constantly telling your trunk that you don’t need it to activate, what is it likely to do? Deactivate.

This also reinforces why I’d like to separate core strength from trunk activation. You can have great core strength but not use it when you slouch. It's a passive process.

So with this in mind, I'd like to ask you this:

Do our daily spinal shapes create the dysfunction that leads to hamstring injury?

What I'm finding clinically suggests it might.

Let's Get (S)talking

I've used Instagram to highlight athlete dysfunction before (AFL footballer, Jaeger O'Meara).

Unfortunately, hamstring dysfunction comes with covert symptoms which make it challenging to highlight with still images. It's impossible to find an image of someone with a stiff back or a poorly activated trunk as you need to feel for them.

I can, however, show you what I believe to be the cause of those symptoms - terrible spinal shapes.

Interestingly, it’s not hard at all to find pics of Cyril Rioli in poor resting spinal shapes.

Obviously these photos of Cyril are just a moment in time and may not reflect his reality. But the pictures show what they show. In fact, every photo I could find of Cyril sitting has him slouching. Take that as you will.

Now compare these shapes to someone like Australian supermodel Jennifer Hawkins.

The difference is stark.

As you can see, Cyril's default shape is very hinged. It's nowhere near as upright and straight as Jen's.

Where To Now?

Despite the amount of time dedicated to understanding hamstring injuries, I'm not yet convinced we are completely out of the dark ages yet.

Clinically, there seems to be a strong, repeatable pattern between poor spinal shapes, low back dysfunction, and hamstring injury. But for something like this to be taken seriously we need good quality research to come in and back something like this up.

Until then I will happily settle for these repeatable and actionable clinical observations.

I'm sure that everyone reading this will have some basic awareness of the importance of good “posture”. But how many actually put in the effort to practice good spinal shapes all the time? Not many, if any.

Our elite athletes may have the best strength, conditioning and rehab staff at their disposal, but when they're not being athletic, what are they doing with their spines?

If you're a recreational athlete consider how much time you spend in less than perfect spinal shapes. If you sit or lean for a living, you may be shocked at how often you're unnecessarily challenging your spine.

It's also important to note that treating spinal dysfunction and improving positional awareness clearly won't cure a hamstring injury on its own. Once injured, it'll still need local treatment and rehab to get going again.

But with all this in mind improving low back function may:

a) prevent hamstring injury

b) speed up recovery

c) reduce the risk of reoccurrence

Conclusion

This may not be news to everyone, but the back seems to matter with hamstring injuries. It may never cleanly predict injury rates but clinical hindsight is becoming rather compelling.

I hope those suffering from any and all hamstring issues read this and feel inspired to take action.

Check this out for yourself or get a health professional to do it for you. Have a go at freeing up your spine and learn/re-learn how to brace it effectively. It may be a missing piece to your rehab puzzle.

Take the time to understand your shapes and postures. It may be sitting-related, it may not. Just keep an eye out.

I’m always looking to broaden my thinking and would love others heading down these paths to reach out and share ideas. I'm all ears and my future patients will thank you for it.

What are your thoughts on the back's role in hamstring injury?