ACL Injury Guide: Prevention, Recovery & The Ankle Connection | Physio Insights (ft. Ex-AFL Star Nic Naitanui)

By Grant Frost · Physiotherapist

•

Last clinically reviewed: 11 October 2025

Table of Contents

of ACL injuries are non-contact - meaning they're potentially preventable through better mechanics.

Understanding ACL Injuries: More Than Just Bad Luck

Many know how devastating an Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) injury can be. There's a long, mentally challenging rehab process and a very real chance you may re-injure yourself again. But as a Physiotherapist working alongside those recovering from ACL injuries every day, I've come to understand we might be missing one crucial piece of the puzzle.

This piece might help explain why ACL injuries occur - and re-occur, beyond current cliches like bad luck and 'moving the wrong way'. From what I see clinically, ACL injuries may have more to do with the ankle than we realise.

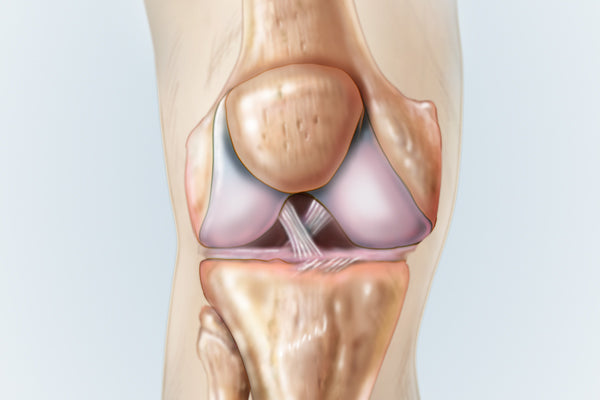

ACL Anatomy & The Injury Triad

The ACL is a robust knee ligament that attaches from the bottom of the thigh bone (femur) to the top of the shin bone (tibia). It works alongside the Posterior Cruciate Ligament (PCL), Medial Collateral Ligament (MCL), Lateral Collateral Ligament (LCL) and Meniscus to support and stabilise the main compartment of the knee.

An unfortunate by-product of an ACL injury is the damage to other structures inside the knee. In many cases, we also see an MCL injury and/or torn meniscus. This is often referred to as the Triad, which can complicate both diagnosis and rehabilitation.

ACL Injury Symptoms & Diagnosis

Recognizing an ACL injury early is crucial for proper treatment. Typical signs include:

- Knee giving way or buckling

- An audible pop or clicking sound

- Intense initial swelling within hours

- Sudden, intense and deep knee pain

- Feeling of instability

The Lachman's test is currently the most efficient clinical test for ACL injuries:

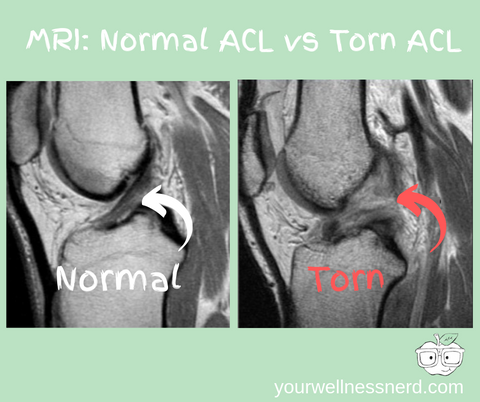

For definitive diagnosis, an MRI remains the gold standard:

Beyond Traditional Risk Factors: What We're Missing

Traditional ACL risk factors include:

- Quadriceps and Hamstring muscle imbalance

- Poor general strength and conditioning

- Previous ACL injury

- Gender (women have a higher incidence)

- Playing on artificial surfaces

While these factors matter, they don't fully explain why 70% of ACL injuries are non-contact. The problem with traditional answers is twofold:

- We promote anatomical differences as 'abnormal' when they're not

- Some traditional risk factors cannot be changed

The Ankle-ACL Connection: The Missing Link

Through my clinical work, I've developed this understanding: Compromised leg mechanics may have the greatest impact on what happens to your ACL. This goes beyond bad luck, moving the wrong way, or being a woman.

So what creates one of the biggest compromises to our leg mechanics and directly sets the ACL up to fail? Ankle stiffness.

How Ankle Stiffness Affects Knee Mechanics

I'm not necessarily talking about ankle muscle tightness here. We're talking deep, capsular stiffness - a "rusty joint." The idea is that stiffness at the joint below the knee forces the entire leg to compensate. Ankle stiffness subtly forces the leg to collapse and rotate inwards to find a way around restrictions. This 'valgus' movement leaves the knee consistently at risk due to its basic hinge design.

This default pattern becomes clearly visible when watching someone land from a jump or perform a deep squat:

The first 17 seconds of this video highlight what a collapsed leg position looks like. Notice how the knees cave inward - this is exactly the pattern that can put the ACL at risk.

The Deep Squat as a Diagnostic Tool

The ideal expression of full lower limb mobility in a deep squat includes:

- Feet straight

- Knees rotated fully out

- Arches maintained

- Heels on the ground

- Back straight

- No sense of falling backward

If your ankles are stiff, there's a high likelihood you won't make it to the bottom with good form. Instead, you'll see feet that turn out, knees that collapse inwards, arches that flatten, and heels that lift off the ground.

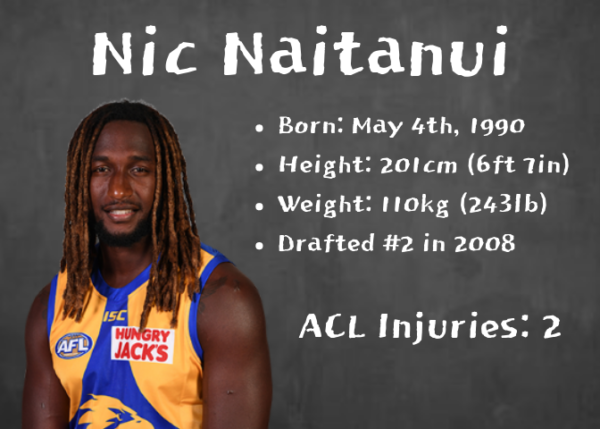

Case Study: Nic Naitanui's ACL Injuries

Nic Naitanui, an AFL Ruckman and incredible athlete, has suffered two ACL injuries. His case highlights what I'm seeing clinically with ACL injuries.

Here's the moment Nic Nat unfortunately ruptured his right ACL in 2018:

Nic Naitanui has suffered a knee injury and will not return today.#AFLPiesEagles pic.twitter.com/A0Z30A2KEy

— AFL (@AFL) July 15, 2018

Notice how innocuous the incident was and the direction his knee collapses. It's even more revealing to look at his movement patterns before the injuries.

This video from July 2017 (almost a year after his first ACL injury and one year before his second) shows concerning mechanics:

Learning the art of flight again...I'm comin' #justdoit #godspeed pic.twitter.com/WuDZqygwvk

— Nic Naitanui (@NicNat) July 13, 2017

Watch what happens to his knees, feet, and ankles at the 15-second, 22-second, and 51-second marks. They violently shunt inwards each time - a carbon copy of the mechanics that led to his ACL injuries.

Here's a picture of him squatting from the very game he most recently re-injured himself:

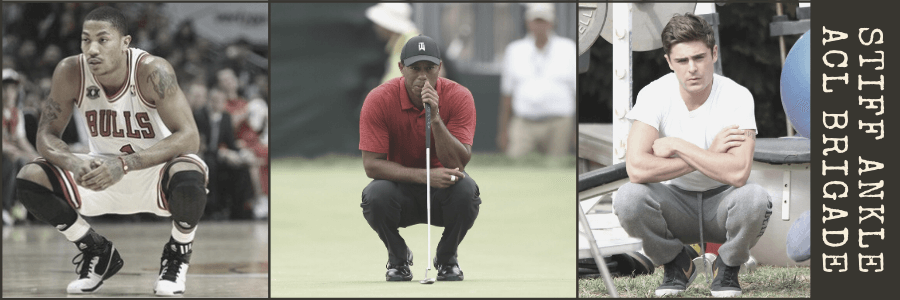

Notice his heels coming off the ground. Clearly every picture needs context, but this can be a of significant ankle stiffness. This pattern isn't unique to Nic Nat - we see similar mechanics in other ACL injury victims:

ACL Injury Prevention Exercises

If you're looking to free up stiff ankles and reduce ACL injury risk, the banded ankle stretch is one of the most important prevention exercises.

Banded Ankle Stretch Protocol

- Hook a power band around your ankle joint

- Step forward with your feet straight and create as much band tension as comfortable

- Bend your back ankle (keeping your knee rotated out - don't let it cave in)

- Hold for 1-2 minutes

- Repeat as often as necessary

Expected Result: You should feel an immediate improvement in squat depth and quality after performing this stretch.

ACL Injury Treatment Options

Treatment depends on the type and severity of the ACL injury:

Partial ACL Tear

Recovery Time: Approximately 3 months

Rehab Focus: Bracing,reduce pain/swelling, restore range of motion, gradually rebuild strength, sport-specific conditioning

Complete ACL Tear/Rupture

Typically requires ACL reconstruction surgery with an expected return to sport around 12 months post-surgery. Interestingly, we are now seeing cases where ruptures ACLs may heal on their own without surgery.

chance of re-injury in the first few years after surgery - highlighting why addressing underlying mechanics is crucial

Comprehensive Rehabilitation Protocol

Here is a comprehensive ACL recovery program.

Strength and conditioning will always play an important role in ACL recovery, but we need to place more emphasis on improving how we move.

I find squat and deadlift shapes to be some of the best ACL rehabilitation exercises to master during rehab. The key is to maintain both a straight, well-braced spine and an external rotation force at the hip (knees out) throughout each movement.

These basic human movement patterns engage all the major muscle groups needed for proper leg function and can be scaled from basic post-op movements to advanced sport-specific training.

Key Rehabilitation Principles

- Remove restrictive handbrakes at the ankle, hip, and low back

- Retrain robust and functionally sound movement patterns

- Progressively build capacity while maintaining optimal mechanics

- Incorporate sport-specific demands only when the foundation is secure

Conclusion: A New Perspective on ACL Injuries

An ACL injury can be devastating, but from what I see clinically, they may not be the sudden, knee-specific dose of bad luck we often promote them to be.

Instead, they may be a failure of already vulnerable leg mechanics to tolerate a situation that, in a perfect world, should pose no threat to your knees.

Key Clinical Takeaways:

- Traditional causes (landing, pivoting, etc.) may expose flaws rather than create them

- Ankle stiffness may be the biggest contributing factor to non-contact ACL injuries

- Hip mobility/control and low back function consistently fly under the radar

- Strength matters, but movement quality matters more

- Deep squats reveal mechanical compromises that put ACLs at risk

The answers to reducing ACL injury rates are right there in front of us in how people move. We just need to take a step back to see them.

This article represents clinical observations from my Physiotherapy practice. Individual cases may vary - always consult with your healthcare provider for personalised medical advice.

Need Personalised Guidance?

If you'd like help trying to uncover the underlying cause of your pain or dysfunction, consider booking an online Telehealth consultation with Grant here!